When the global COVID-19 pandemic burst into our lives, many of us found ourselves in the strange situation of being extremely dependent on official government sources. We needed someone to navigate us through this unsettling and unexpected crisis. Trust in governments surged globally somewhere in March-April 2020. However, recently both the level of that trust, and in parallel, the levels of trust in the media have started to decline. That has provided space for more ‘corona-deniers’ to be heard and seen, despite official figures which show that worldwide more than 11 million have had the disease and more than 500 thousand have died from it.

What’s interesting is that this loss of trust has happened in several countries, for different reasons. Take the United Kingdom. The public’s trust in government fell sharply at the end of May according to a poll from the University of Oxford’s Reuters Institute, conducted by YouGov. Now less than half of Britons trust their government.

The steepness of the decline – from 67% to 48% – was remarkable: “I have never in 10 years of research in this area seen a drop in trust like what we have seen for the UK government in the course of six weeks” the institute’s director is quoted as saying. Much of the British media was full at the time of headlines on the behaviour of the UK prime minister’s senior advisor, Dominic Cummings, who did not resign even though he’d apparently flouted lockdown rules is some rather flagrant, even ridiculous ways.

I also noted that this poll also found a sharp increase in the percentage of people who were concerned about actual ‘false or misleading’ information about COVID-19 emanating from the UK government. Maybe that also helped to set the stage for scenes like this at the British coast in recent weeks, where people crowded, without masks, to enjoy the sunshine.

What is in Uzbekistan?

Some five thousand kilometres away in Uzbekistan, the trust issue has also serious potential consequences. But is related instead to people believing that the government has in fact been too strict, too serious in the ways that it has tackled the corona crisis. The country has taken strict measures, such as suspension of commercial flights and railway travel, and traffic restrictions, and the lockdown has been extended until August 1. The most recent figures show that the number of confirmed cases is over eleven thousand while forty-nine people have died. This seems to indicate a relatively low death rate, which has set the stage for ‘covid-19 disbelievers’ to argue that this whole outbreak in Uzbekistan is a cover for the government to attract foreign aid. They think it’s a farce, with corruption, not disease, at its root.

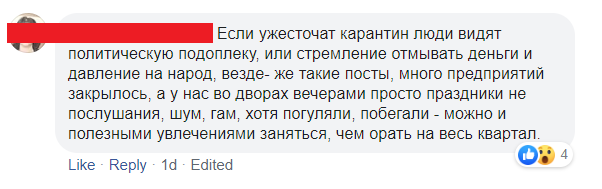

The deniers are spreading their comments across social media. I went through some Facebook posts from popular online news media and traced the activities and commentary of those who deny the situation. They are visible on almost every post about the corona situation in the country. For example, under the news “34th patient died from coronavirus” one user writes, “If the lockdown measures are tightened up, people would see political underlining or the opportunity for money laundering and putting pressure on people…Many factories have been closed while in our yards people are celebrating, gathering in big companies and shout out loud…”

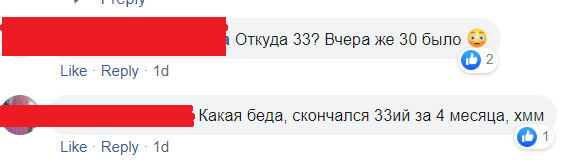

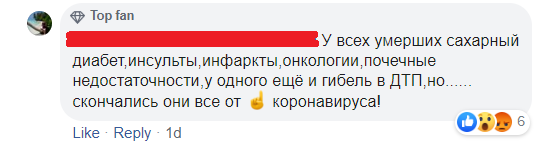

There were also other comments where people point to the official death toll as evidence that the disease is not very serious, ironically suggesting that 33 deaths is “a lot”. One striking comment was written by a user who says “all those passed away had diabetes, strokes and heart attacks, cancer or kidney disease. But all of them died from coronavirus!” On the other hand others were arguing that the death rate must be way higher, and claiming the government is silencing the real numbers.

Can media rebuild trust?

It feels in some ways like governments really can’t win in this situation. And when people don’t trust their governments – for whatever reason – the media also is tarred with the same brush. It’s a global phenonmenon. We’ve recently explored how similar conspiracies about this global pandemic reverberate across different countries with Sabine Berzine from ReCheck.

Olasumbo Modupe also shared with us, how “some people [in Nigeria] believe the government just want to use the pandemic to get funds from world health leaders.” To counter these misconceptions, in her work as a TV journalist, Olasumbo suggests that the trust issue needs to tackled head on: “we don’t really have videos or pictures of people who’ve been affected. When the chief of staff was infected and died, most people still think it was a lie. So many misconceptions. It is very very difficult to achieve more. What we actually need here is to see patients for testimonies, this will help flatten the curve as well as stop stigmatisation and improve adherence to precautionary measures.”

In case of Uzbekistan, such testimonies from patients could also help, I believe. Even if they do not have access to isolation centers and hospitals, journalists should demand that health authorities provide more information that people would trust.

It may also be a good idea to explain to our audiences what is happening in neighbouring countries. For example, the confirmed cases in Kazakhstan surpassed fifty thousand, and the number of deaths is 264. Taken along with the shortage of beds in hospitals, lack of essential medicines, and complications with the testing, this is an alarming situation. Clear factual reporting on what is really happening in different health systems may be the best way to rebuild trust with our audiences.

Anastasiya Pak